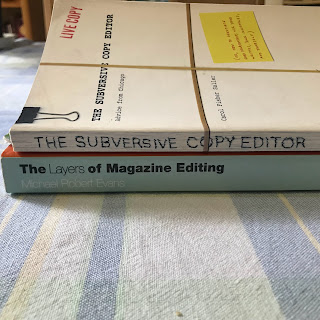

I've just discovered this blog post: it was in my draft folder, almost completely finished, but never published. I wrote it over a year ago. It think it's time to let it out into the wild. Of course most of you aren't editors, which is probably why I didn't end up publishing it. But, I've been reminded that many of us have to edit our words or other people's words, whether we identify as an editor or not. In the last year I've read The Subversive Copy Editor by Carol Fisher Saller. She says,

"In the routines of almost any office job, a worker is likely to be responsible for a chunk of writing, and in any chunk of writing there is likely to be a problem. Solving problems with writers is what copyediting is."(p 3)

I like that: lots of us are editors, whether we think of that as part of our skill-set or not. I also like the idea that editors are problem solvers. That's what I love to do: solve problems!

By the way, it's an excellent book. I've underlined many passages in it. For example:

Editing "matters because inaccuracies and inconsistencies undermine a writer's authority, distract and confuse the reader, and reflect poorly on the company...Discriminating readers look for reasons to trust a writer and reasons not to . . . [We] help the writer forge a connection with the reader based on trust—trust that the writer is intelligent and responsible, and that her work is a reliable source." (p 10)

This book is about doing a good job as an editor (tonnes of practical hints about how to organise your work etc.) and but also also how to build a good relationship with writers. It's one of those books I'd love to have read before I started work as an editor—I had to learn so much by trial and error!

Editors also need to build trust with their writers and that's not easy to do when you don't have a face-to-face relationship with them. I look back now and realise that most of the difficulties I had early on was that writers didn't trust me. And quite possibly I needed to do more to gain their trust than I did.

The three key words she emphases in her book are carefulness, transparency, and flexibility.

I could go on and on about this book, but anyway, if editing is part of your job, I recommend you grab this book and read it. It'll be worth your while. You can skip past bits that don't apply to you, but a lot of it is very relevant if editing in some form and working with others with their words is part of what you do. Oh, and there's a chapter just for writers too!

Here is what I wrote in March last year:

Last week I taught a short session at a non-fiction book-writing workshop. Online, of course! I first talked about working with editors and, obviously, gave advice about how writers could work well with editors. At the end of that I asked for "bad experiences" with editors. I was shocked. My advice to editors, is the same as what I gave the writers (in this blog post): be professional and treat this work as a team event.

The best quote I've seen about editing was in an acknowledgement of a book I picked up recently. The author noted that the editor "was both an enthusiastic supporter of the author and a faithful advocate for the reader." This succinctly explains the careful tension that an editor must work under in order to do good work. I don't believe the best editor is one who has the best understanding of English. I think the best editor is one who can keep these two elements in mind while working.

"The relationship between writer and editor can be as complex as any marriage. The common perception seems to be that the editor holds all the power. [Magazine editor talking to writer] 'Do it my way, or forget about the assignment!' he bellows, 'And forget about ever working here—or anywhere else—ever again!' (The Layers of Magazine Editing, Michael Robert Evans, p. 123-125)

In reality, the relationship is, or should be, much more balanced than that. Yes, the editor can block the publication of an article...[but] the last thing an editor wants to do is leave a good writer feeling abused, mistreated, neglected, or otherwise."

"Editors don't hold all the power. And they know that. So they work to keep their writers happy." (or they should!)

It is the "tension between nurturing and pressuring that makes the writer-editor relationship so delicate and challenging."

My philosophy is to remember whose name will be on this work at the end of the day. If it is the writer's name, then they hold more power than I do, though hopefully we've build a respect for one another that they at least hear my opinion and take advice. The caveat with that is that there might be other considerations, especially if this writing represents a group larger than the writer. For example, the magazine I edit is published by an organisation, and I can't let writing that violates their name go into the magazine. I work in social media for my mission organisation and can't let writing go out under that name, or on the website, that goes against its principles.

What I do is somewhat different to book editing, in that I have fairly strict deadlines and word-limitations to keep to. So, sometimes I have to choose not to publish something, or seriously shorten something because of these limitations. I also have a team of people who help me with this publishing work, I have occasionally rejected an article because I deemed it unfair to demand my team do the excess amount of work that would be required to publish that author's work.

So here are my tips for any out there who edit other people's work:

- This is not your work, it is the author's and will have their name on it, don't ever lose sight of that. Your goal is to make their writing shine. (The caveat to that from The Subversive Copy Editor, is that "it's not the author's right to offend or confuse the reader, defy the rules of standard English, fail to identify sources, or lower the standards of your institution.")

- Be kind, but not dishonest. Writers, especially new or inexperienced writers can take changes to their work personally. It's a good policy to seek ways that you can legitimately encourage the writer.

- If you think big changes are needed (eg. removing large amounts of content, changing structure, significant change in tone or audience or main focus, rewording larger segments), go back to the author and see if they can make the changes themselves. Explain your reasons. The best editors do as little rewriting as possible.

- If rewriting is necessary, be willing to go back and forth on it with the author, giving clear direction as to what you're expected.

- Editing is not black and white. A number of the changes you will want to make are instinct or opinion. There is usually more than one way to express something. So be willing to revise your decisions if a writer is adamant.

- Good communication with writers is vital. Try to keep your communication succinct: not long-winded, but also not multiple emails/phone calls.

- Be clear about what you want. For example, word length, audience, main emphasis, due date, tone, even how they format the article before sending it to you. This might chafe some writers, but it is better to have these things clear and avoid wasting the writer's time and then having to waste more time afterwards with major rewriting or worse. For this reason with Japan Harvest magazine, I ask for proposals before people write, so I have a chance to direct them in their writing before they've invested valuable time into writing.

- Keep your readers in the forefront of your mind. Your goal is to help the writer communicate clearly with them.

- Make sure you check your changes with the writer before you publish.

- And again: be professional. That means be respectful, don't take things personally, do what you say you will do, and don't be unreasonable.

As a Christian I do my best to build a gracious relationship with writers. After all, as a Christian I am called to have a character full of these: "But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control" (Gal. 5:22–23 NIVUK).